Readings Carlton bursting at the seams for the launch of Back to Broady and The Many Ways of Seeing

On Wednesday 9 August, an usually warm Melbourne winter evening, an impressive group of fellow writers, family and friends gathered at Readings Carlton to celebrate the launch of 'companion' memoirs from the newly established Ventura Press imprint Peter Bishop Books - Nick Gleeson's, The Many Ways of Seeing, co-authored with Peter Bishop, and Caroline van de Pol's, Back to Broady.

Caroline and Nick grew up next door to each other and lived side by side for nearly twenty years in the working-class suburb of Broadmeadows. They have remained close friends and have produced very different memoirs about family and friendship with stories both intertwined and quite separate.

A ‘cathedral of books’ was how Peter Bishop described the venue of Readings Carlton, for vision impaired members in the audience, and he went on to describe the ‘sea of faces’ for Nick Gleeson and his brother Maurice, who are both totally blind. Peter then read from The Many Ways of Seeing and spoke with Nick about his most recent adventure, crossing raging rivers in the remote wilderness of New Zealand. Caroline then read from Back to Broady.

Readings agreed it was a full house and one of the largest events they had hosted. This only inspired Maurice Gleeson, OAM, who officially launched the books and spoke about the significance of companionship in our lives.

A huge thank you to everyone who came and supported Back to Broady and The Many Ways of Seeing, Maurice Gleeson for launching the books, Patti Green for taking these amazing photographs, Readings Carlton for being excellent hosts and a huge congratulations to our amazing authors, Caroline van de Pol, Nick Gleeson and Peter Bishop.

Peter Bishop and Ventura Press director and publisher, Jane Curry.

Maurice Gleeson, Caroline van de Pol, Nick Gleeson and Peter Bishop.

Long-time friends and authors Caroline van de Pol and Nick Gleeson.

Peter Bishop reads from the book he co-authors, The Many Ways of Seeing.

Nick Gleeson and Peter Bishop talk about The Many Ways of Seeing.

Caroline van de Pol reads from her book Back to Broady.

Nick with his friend and guide dog Unity.

Maurice Gleeson OAM, brother to Nick and long-time friend of Caroline's, officially launches Back to Broady and The Many Ways of Seeing.

The van de Pol and Egan families celebrating Back to Broady with Caroline.

Photo credit: Patti Green

Ventura Press to publish Lisa Dempster's travel memoir Neon Pilgrim

Ventura Press, one of Sydney’s leading independent publishers, is delighted to announce it will be publishing Lisa Dempster’s debut memoir, Neon Pilgrim, on 1 August 2017.

Neon Pilgrim is Lisa’s refreshingly honest and inspiring story of walking back to health on the henro michi, an arduous 1200-kilometre Buddhist pilgrimage through the mountains of Japan.

First published in 2009 by Aduki Independent Press, the book received limited distribution across Australia.

“The opportunity to republish the remarkable Lisa Dempster’s Neon Pilgrim is the highlight of our 2017 list,” said Jane Curry, director and publisher of Ventura Press.

“Lisa’s memoir of her pilgrimage on the henro michi encompasses the universal truths that will always resonate with readers: loneliness, spirituality, humanity and belonging, and we are thrilled to be able to share her incredible story with a wider audience.”

Lisa Dempster, the artistic director and CEO of Melbourne Writers Festival, said she is a firm believer in the importance of independent publishing, and is thrilled to be working with Jane Curry to bring Neon Pilgrim back into print.

“It's been a rewarding process to work with her visionary and supportive team at Ventura Press to reimagine my memoir for a new audience,” she said.

Appealing to fans of Wild by Cheryl Strayed and Tracks by Robyn Davidson, Lisa said anyone who has ever been at a crossroads in their life will appreciate her memoir, and hopes it will continue to open up the vital conversation around women and mental health.

“And of course, I hope it encourages adventurous-minded women to hit the trails – if I can do it, anyone can!” she said.

ABOUT LISA DEMPSTER

Lisa Dempster is the artistic director/CEO of the Melbourne Writers Festival. Previous roles have included Asialink fellow at Ubud Writers & Readers Festival, Director of the Emerging Writers' Festival, founding director of EWFdigital (now Digital Writers' Festival) and publisher at Vignette Press. Lisa has travelled widely in search of literary and other adventures.

Peter Bishop Books

Ventura Press is delighted to announce its latest imprint: Peter Bishop Books. Born as a collaboration with Bishop, the imprint will present a catalogue that aims to rekindle the intimate relationship between author and reader, a unique and inimitable dynamic that imbues reading with a magic not found in other art forms.

With over 17 years’ experience serving as a writing mentor and creative director of Varuna, the Writers’ House, Bishop aims to curate a unique catalogue of works that reflects his keen eye for spotting and fostering talent. The imprint will publish a range of works across a diverse variety of genres, united by the desire to create and tell truly memorable and enduring stories.

Peter Bishop Books will launch its first title, The Many Ways of Seeing by Nick Gleeson and Peter Bishop, in June 2017. Although becoming blind at the age of seven and growing up in the working-class suburb of Broadmeadows, Victoria, Gleeson has led a truly remarkable life, from climbing to the base camp of Everest and the summit of Kilimanjaro, to running marathons, and competing as a Paralympian.

The Many Ways of Seeing reflects on Gleeson’s lifetime of achievements, as well as his relationship with Bishop, as the two tell this unique story in their own unique way. In a blend of memoir, conversation and insights into the writing process, Gleeson and Bishop weave an inspiring tale of surviving hardship, building trust, and reflecting on the relationship between writer and mentor.

The second title to be published will be Back to Broady by Caroline van de Pol in July 2017. In a book that in many ways is the ‘twin’ or ‘sibling’ to The Many Ways of Seeing, Gleeson’s childhood neighbour and friend Caroline shares her own powerful memoir of growing up in 1960s Broadmeadows, Victoria. This is Caroline’s compelling story of her fight through disadvantage in a large, chaotic Irish Catholic family, and the incredibly moving experiences that have helped her walk the fine line between survival and surrender.

The Better Son long-listed for The Indie Book Awards 2017

We’re extremely excited to announce that Katherine Johnson’s gripping novel The Better Son has been long listed for the Indie Book Awards 2017 fiction list. This is an astounding achievement for Katherine and her hauntingly beautiful book. The Better Son is a richly imaginative story that explores the complex nature of relationships, the power of forgiveness and the enthralling beauty of the unique Tasmanian landscape.

Other great titles listed alongside The Better Son include Hannah Kent's The Good People, Emily Maguire's An Isolated Incident, Liane Moriarty's Truly Madly Guilty, Georgia Blain’s Between a Wolf and a Dog and Inga Simpson's Where the Trees Were.

The Shortlist will be announced on 16th January 2017. The category winners and the Overall Book of the Year Winner will be announced on Monday 20th March 2017 at the Leading Edge Books 2017 Conference.

A big congratulations to Katherine for this fantastic achievement!

More information about the awards can be found here.

Melbourne Launch of Rebellious Daughters

On Thursday 4th August, at The Long Room in Melbourne, family, friends and contributors came together to celebrate the launch of our fantastic anthology, Rebellious Daughters. Introduced and launched by our editors, Maria Katsonis and Lee Kofman, with readings from two of our contributors, Leah Kaminsky and Jamila Rizvi. It was a wonderful evening full of extraordinary women. We are very proud to finally see this beautiful book on the shelves.

Above: Co-editor, Maria proudly introducing Rebellious Daughters.

Above: Co-editor, Lee Kofman, officially launching Rebellious Daughters.

Above: Leah Kaminsky, contributor, reading an extract from her story, 'Pressing the Seams'.

Above: Jamila Rizvi, contributor, reading from her section, 'The Good Girl'.

Some of our wonderful contributors (Left to Right): Jamila Rizvi, Rochelle Siemienowicz, Maria Katsonis, Lee Kofman, Jo Caro, Amra pajalic, Nicola Redhouse, Leah Kaminsky, Silvia Kwon.

Rebellious Daughters is out now, to purchase a copy click here.

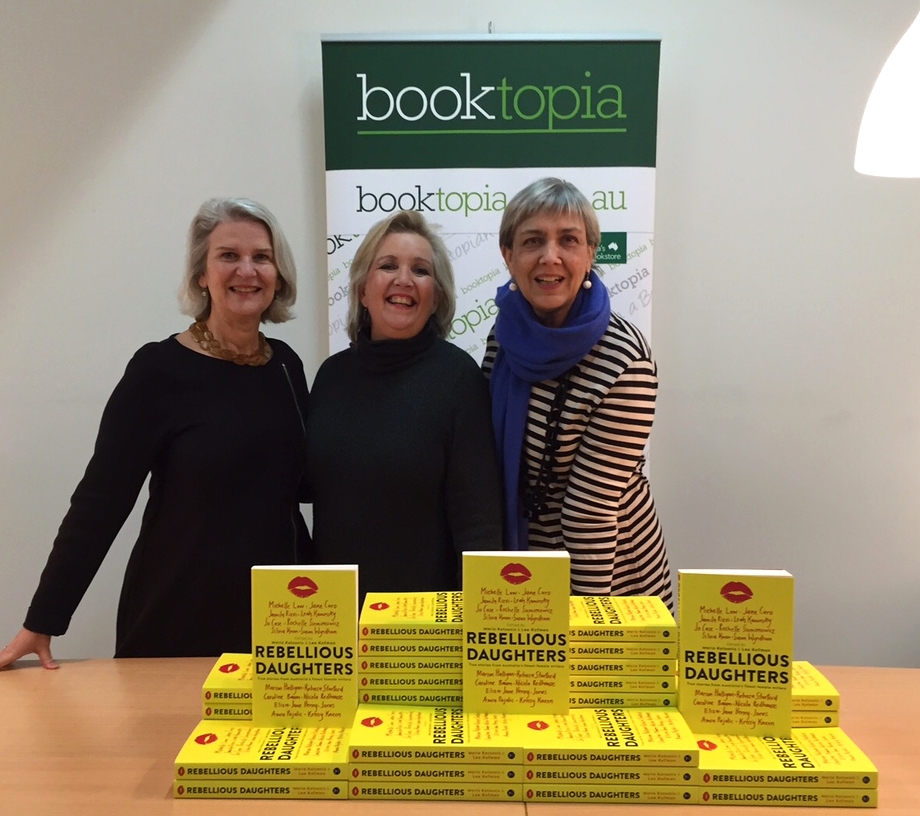

Booktopia Podcast with Rebellious Daughters contributers

Today, three of our Rebellious Daughters contributers, Jane Caro, Susan Wyndham and Caroline Baum were interviewed for The Booktopia Podcast. Here are some behind the scenes photos as we watched them record and sign some exclusive copies. Head over to Booktopia's Podcast to listen.

An extract from Father Time

Brilliant, readable and revealing. One day we will live in a different world, and this will be one of the books that made it so. Steve Biddulph, author of Raising Boys

First published in 1998, Father Time revolutionised fatherhood by helping men work toward what really matters – balancing work and family.

Read an extract below.

Brilliant, readable and revealing. One day we will live in a different world, and this will be one of the books that made it so. Steve Biddulph, author of Raising Boys

First published in 1998, Father Time revolutionised fatherhood by helping men work toward what really matters – balancing work and family.

Read an extract below.

CHAPTER ONE

LOST FATHERS

We are within a generation of losing forever a sense of what fathering is all about. A plastic shell-like doll, made for TV and economically sleek, is replacing the fully-rounded figure of the nurturing and protecting father in traditional society. This is the ultimate form of a model which first took shape at the time of the Industrial Revolution. It is inherently corrupt and is destroying our families and our lives.

THE DISTANT RELATION

While men continue to produce children physically, increasingly, the father is becoming a distant family relation. An increase in work hours for much of the population has meant that fathers are less often at home. Moreover, when they are at home their children are asleep or the fathers are still in work-mode, finishing off some left over office task. Less time is being spent by fathers not only sharing their knowledge of life but more importantly, helping their children’s emotional development.

It’s true that many men also play a fatherly role for children who are not their own. Men who coach sporting teams and male teachers often provide children, especially boys, with the male bonding that is so important to a child’s development. But there are generally fewer parents involved in community activities with children than there were some years ago.

MANLESS CLASSROOM

The teaching profession is also rapidly losing its male members. The fact that society so undervalues the group of people who, apart from parents, have the most significant influence on future generations defies logic. Many Asian countries which believe, as we claim to do, that children represent the future actually put their resources behind education. Funding is seen as a high priority and not an area for constant reduction. But in Australia the poor financial rewards mean that in public schools we have fewer male teachers than female and their numbers are constantly declining.

While teachers, whether male or female, have an equally significant influence on the development of the young children must be given the opportunity to build healthy relationships with adults of both sexes on a regular basis. This is as important at school, where they spend most of their day, as it is at home. Of course this does not mean that thrusting children into random situations with adults is at all healthy. What is required is an environment where stable, healthy relationships can develop between them.

WRONG ROLE-MODELS

Together with the fact that men as fathers or surrogate fathers are spending much less time with children than they should, is the increasing emphasis on materialism in its ugliest form. Newspapers are full of ‘heroes’ whose only achievement has been to make money. Little attention is paid to how they accumulated their wealth, whether their business practices are ethical and moral, whether they are good family men, or whether they have done anything for the community. Money has become the balm with which the popular press anoints its idols. We have lost the ability to see people as real human beings with both good and bad points or judge them on the depth of their character.

The elevation of such dubious types to star status gives us very poor role-models to follow. Some people who are sufficiently strong-willed and independent to keep their attitudes and values intact will be able to find their own way through these confusing influences. The rest of us, however, do look for someone who can act as an example to help guide us through life. Unfortunately, the media do not take their responsibilities seriously enough and keep coming up with false models for us to emulate, based only on the measure of financial success.

WHOM DO I TURN TO?

So where does a new father turn to learn the skills he is going to need? As a soon-to-be-father in 1989, I wandered into a large city bookstore in search of some books that could help prepare me for what I was about to be thrown into. I found a fair range of books dealing with a baby’s development and the mother’s physical and emotional development both before and after giving birth. There were very few books which even acknowledged that the father had a role to play. A couple were semi-humorous, introducing fathers to the pleasures of baby vomit, midnight screaming and baby diarrhoea. But there was nothing to help me understand better what I should be doing, and how I should be dealing with my own thoughts and emotions.

Attending ‘baby classes’ reinforced this impression. While it was acknowledged that the father had some role to play—mainly limited to impregnation and assisting his wife during labour—nobody seemed to be interested in supporting him as an active, informed participant in his child’s development. The Department of Health organises ‘playgroups’ to allow new mothers to meet up and share their experiences of child-bearing. But there were no forums where fathers could engage in any detailed discussion about the arrival of their child and what it meant to them. This of course continued a long tradition of men dealing in silence with major events in their lives, so it was probably not surprising to find such a lack of services for the father.

The result is that the father who wants to find out more about his new role becomes quickly discouraged. He goes back to being the uninformed support-assistant to his wife—as though he has no other function than that of support. Of course, supporting your wife is a key role and one that most fathers accept as an important task, though there is always the odd exception. I recall one senior executive at Microsoft who used to boast about his dedication to the company by telling people that he was away on business for the birth of all three of his children. Perhaps he will wake up one day and realise he has missed one of life’s most magical and important moments (three times!) for the sake of better revenue performance. A high price to pay.

PASSIVE FATHERHOOD

Restricting the father’s role to support undervalues the part he can and should play in the birth and development of a child. It also presupposes that fathers have either little interest in what is happening or little of value to add. One could be excused for thinking that fathering is nothing more than a biological process. Many fathers’ personal involvement with their children is prescribed by a tight agenda drawn up by their wives, almost like a manual on how to be a dad until mum gets home. The common attitude that mothers should provide explicit instructions needs to be reviewed. Is it that men are genetically incompetent when it comes to looking after children or that they do not have the interest? Part of the problem lies in what society has accepted as normal behaviour. This has resulted in a pattern that has become perpetuated.

In a study some years ago E.R. Goldsmith and J.H. Greenhaus looked at differing models of work and family. They reported on earlier research by Joseph Pleck which suggested that social norms ‘permit’ women to forego work activities in the face of family responsibilities, whereas men are permitted to forego family activities in favour of work commitments. Fathers now use part of the time they would once have spent with their families to go to work, just as it has been considered normal practice for women to give up work to have children. The establishment of social norms that put a father’s work ahead of his family responsibilities creates a false sense of what society needs from fathers.

FACTORIES AND FATHERING

The effect of the Industrial Revolution on fatherhood has been well documented by many writers, including Steve Biddulph in Manhood and Adrienne Burgess in Fatherhood Reclaimed. In the second half of the 19th century as industrialisation intensified, fathers increasingly left the traditional home environment to work in the new factories. The family structure changed dramatically. The father was now no longer at home during the day and thus children missed out on the importance of his influence during their growing years. According to Burgess, early 20th century family experts declared that this new form of part-time fathering was actually desirable, somehow allowing a weary father to return home from the day’s work with a fresh approach to issues in the family domain.

The detached father who was created during the Industrial Revolution and still exists today was a new phenomenon. Previously, as many accounts of the time make clear, fathers would show a great deal of public affection for their children, nursing their babies and playing with them whenever they could.

DUAL PROVIDERS

Men are no longer the sole providers of resources for the family. While this is a generally positive trend, it nonetheless removes what has been for centuries a major characteristic underpinning the role of the father. It needs to be replaced with something that men can identify within defining their role.

As a result of the increased participation of women in the workforce, the provider role is now split and the father is no longer the major influence on the formation of a child’s view of the outside world. The fact that the mother is now as significant an influence is again a very healthy development, in that it ensures that children gain the benefit of at least two major sources of influence in their early years. As they grow older the number of possible influences on them grows and the role of both parents declines, particularly that of the father. Hence the father’s position in the family needs to be redefined in a clear way, giving a positive lead on what his responsibilities now are. Historically fathers have provided a strong developmental role with regard to their children’s work. In the second half of the 19th century in the UK more than fifty per cent of children entered their father’s trade.

Clearly the children were being trained into particular trades or professions by their fathers; long hours were spent ensuring the child picked up the skill that would allow them to become employable in their father’s trade.

Yet with this concentration of time spent with their fathers these children were also learning skills other than those focused on a particular trade. Fathers were able to impart life lessons to their children and children were able to develop very strong relationships with their father.

While the trend away from ‘following in your father’s footsteps’ is healthy for many reasons—not the least allowing a child to develop a truly independent life mapped by their own interests—we also lost this sense of a father providing ‘life education’ to their children. It is the loss of this second level of education that is problematic for today’s society.

SYMBOLIC FATHERS

One of the most negative attitudes towards fatherhood I have come across was that of the early child psychologist D.W. Winnicott, who followed the popular view of his day that the father was really most important as a symbol. His role was to ‘turn up often enough for the child to feel he was real and alive’. So much for any concept of involved fathering.

In discussions with executive groups I have heard a similar view expressed. Many executive fathers say explicitly they believe it is both right and proper for the children not to see a lot of their father. Comments such as ‘leaving them to their own devices builds self-esteem and individuality’ are common, ignoring the fact that all research on the subject indicates that such outcomes are not the result of leaving kids alone.

Too often fathers look at their responsibilities purely in the light of their own experiences. Such views are irrational, given the changes that have occurred in society over the last forty years. Harking back to a frequently faulty memory of one’s own childhood is no help in coping with the problems of fathering today. Some men argue that because they were brought up by their fathers in a particular way and turned out well, their children will do likewise with the same treatment. This is like saying, ‘When I was young my father used to beat me with a cricket bat and I survived, therefore I can beat my kids.’ The fact that some children whose fathers spent little time with them, showed them no emotion or physically abused them, grew up with no apparent emotional scars does not mean that such neglect was right.

One father I know, who is a real workaholic and is rarely home in time to see his children, defends his approach by using this logic. ‘My father used to work long hours and I never saw him and yet I turned out all right, so I think my kids will too.’ This sounds more like a shallow justification of his obsession with work than a well though-tout decision on what is best for his kids. What should be done is to combine the positive aspects of your past with some firm ideas of your own on what good fathering should be about.

ALL ON THEIR OWN

The effect of children spending time alone must be taken into account. In the book The Time Bind, A.R. Hochschild quotes a study of nearly five thousand eighth-graders in the US and their parents which found that children who were home alone for eleven or more hours a week were three times more likely than other youngsters to abuse alcohol, tobacco or marijuana. This was true for both upper class and working class children. Research on adults who had been left home alone as children suggested that they ran a far higher risk of developing ‘substantial fear responses’— recurring nightmares, fear of noise, fear of the dark and fear for their personal safety. Hochschild states:

In the grip of a time bind, working parents redefine as nonessential more than a child’s need for security and companionship. The blockbuster film, Home Alone, in which a child left by himself emerges as a heroic everyboy, masks the anxiety that infuses the subject of children home alone with upbeat denial. One husband in Amerco commented, ‘We don’t really need a hot meal at night because we eat well at lunch.’ A mother wondered why she should bother to cook beans for her children when her son didn’t like them. Yet another challenged the need for children’s daily baths or clean clothes: ‘He loves his brown pants. Why shouldn’t he just wear them for a week?’ Of a three-month-old child in nine-hour daycare a father assured me, ‘I want him to be independent.’

In the study of the giant Amerco firm in 1990, to which Hochschild refers (although the name was changed in the book to protect the company), it was found that twenty-seven per cent of children between the ages of six and thirteen stayed home alone while both parents were at work. Of course twelve-year-olds can look after themselves physically when they get home from school, but like all children they basically need to share their experiences and talk about their problems during the day. By the time 6 or 7pm comes around children no longer have the sense of urgency to discuss their problems or, perhaps more seriously, they have internalised the problems as a result of having no outlet.

SURROGATE SERVICES

In the past the mother was around not only to provide the services required after school but offer the love, affection and understanding which is difficult for even the most dedicated childcare worker to give. Services abound to help both parents maintain their careers and also have their children’s needs attended to. In America, for instance, Hochschild refers to ‘Kids in Motion’ in Chicago which provides transport to take kids from school to sport or music. ‘Playground Connections’ in Washington DC matches ‘play-mates’ to one another. In several US cities children call a 1-900 number to contact ‘Grandma Please’. There they can make contact with an adult who has time to talk to them, sing to them, listen to their problems, help them with their homework or just make them feel wanted. ‘Creative Memories’ puts family photos in albums, along with descriptive captions.

These services are a poor substitute for real parent-child interaction. What is lost in this business-like approach is any understanding of a child’s feelings and emotions or the role such activities play in providing an opportunity for parents and children to communicate. Taking children to after-school sport is not merely a taxi service. As well as enabling them to talk about the day’s events with the parent concerned on the way to the venue, it forces the parent out of the work environment. A father who no longer has to leave work by 5pm to take his son to football because he knows someone else will make sure Johnny gets to the oval on time is unlikely to leave work at 5 pm to watch Johnny train.

Increasingly the father is not required to be part of the daily running of his children’s lives. He is also seen as non-essential from a ‘provision of service’ point of view. Nobody seems to care about the child’s, or father’s, need for the love and bond that they can share.

PARENTS BUT NOT CITIZENS

Parental involvement in their children’s lives is diminishing, along with allied social responsibilities. According to the Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, as quoted by Hochschild, the proportion of Americans reporting that they had attended a public meeting on town or school affairs in the previous year fell from twenty-two per cent in 1973 to thirteen per cent in 1993. Membership in organisations such as the Red Cross, Boy Scouts and Lions Clubs has fallen as well. A similar pattern is also discernible in Australia.

At my daughters’ school there are over 1,100 students. That would suggest there would perhaps be around 800 sets of parents (allowing for members of the same family being at school and for single-parent households). Parents’ and Citizens’ Association (P&C) meetings, where major issues about the school and its plans are discussed, are regularly attended by fewer than fifty people. Unfortunately, it is roughly the same fifty people who organise the major events within the school. It is not that the only parents who care for their children are those who attend the meetings but work pressures mean that it is easy to assume ‘the school will run by itself’.

One mother who had a son at the local public school moved him to a private school in Year Two. She told me that she intended to become involved in activities at the new school even though she had shown no interest in helping out at the public school. When I asked her the reasons for the change of heart, she told me the parent group at the private school offered both her son and her husband opportunities to create relationships which would be of use during their lives. Her motivation was not so much to help the school but to further her own social ambitions.

MISSING MOTHERS

The problems resulting from children being left alone are clearly not wholly brought about by fathers being focused on work ahead of their families but also by the greater part women now play in the wider community. The fact that stay-at-home mothers have been able to keep the family together in the past does not mean that they should be ‘motivated’ out of the workforce as some politicians would prefer. What it does suggest is that for quite some time we have lived with an unbalanced home environment, which has only held together because women were at home. As we have seen, the underlying problem of fathers not being involved has been with us for the last couple of centuries. Many fathers also regard providing the money to run the household as a testament to their love and commitment. But as will later be discussed, this is more often an excuse for not spending the time and energy which is really required for good fathering.

FATHER TIME PAYS OFF

There is a strong correlation between the time a father spends with a child and the latter’s development. As Burgess notes:

Right through adolescence and in many different ways, the benefits to children of positive and substantial father involvement can be measured; in self-control, life skills, and social competence. Adolescents who have good relationships with their fathers take their responsibilities seriously, are more likely to do what their parents ask and are less limited by traditional sex-role expectations. The boys have fewer behavioural problems in school, and the girls are more self-directed, cheerful and happy, willing to try new things. Among adults, both men and women, the strongest predictor of empathetic concern for others is high level of caretaking by their fathers when they were little. Father involvement is also one of the major predictors of whether adults in their twenties will have progressed, educationally and socially, beyond their parents.

Research has repeatedly found that when fathers spend committed time with their children, the benefits are enormous. Among seven to eleven-year-olds receiving such attention, for instance, there is a much lower incidence of delinquent behaviour, while older children are more likely to go on to higher education and generally have higher career aspirations. Yet all the evidence points to less time being spent between fathers and children.

An interesting trend may also suggest that there exists a level of parental guilt with regard to time spent with children. In a survey of pre-schoolers in the US it was found that at Christmas time children asked for, on average, 3.4 presents and yet were given 11.7 presents by their parents. I believe that there is a direct correlation between lack of time spent with children and the increase in such ‘guilt’ presents. All children love toys and the receipt of an unexpected toy will bring the parent an immediate positive response from the child. All is well, broken promises recovered: not so. Firstly, the pattern being established is very unhealthy for both parent and child. The parent begins to believe that material goods can be used as a replacement for time spent with the child, while the child is being taught that the parent believes a present makes up for a commitment to spend time together. The lasting effect of a particular toy is very small. The lasting effect of time spent developing a relationship with a child is significant and lifelong.

THE SCREEN

Family time today is often defined by each family member engaging with their own screen (smart phone, Ipad, laptop, TV) watching their own content even when they may be in the same room together.

For very young children it’s easy to switch on cartoons in the morning or give them an Ipad (which of course is an educational item…isn’t it?) to keep them entertained and quiet. The fact is, however, that watching TV in the morning affects a child’s schooling by modifying its initially active brain pattern.

Night-times are cloaked in the seriousness of the evening news with sitcoms or personal content viewing to follow.

There is something quite strange about families sitting around a TV set at night and apparently enjoying each other’s company, but without any of the banter and chitchat that used to characterise home life. It is as though families have outsourced their normal intercourse to the television sitcoms, YouTube, Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram.

The accessibility and availability of content on your smartphone means that you never have to just sit and think or sit and talk. You can always be wired and always be plugged into content that you want to engage with. This level of specialisation has benefits as it allows individuals to pursue their own areas of interest but it also continues to create insular silos within the family home.

Communication is lost when families sit down and let one or more screens engage the family. It also ensures that children stay nice and quiet, if not catatonic. My own experience is that when I came home from work and the kids were at school and they had not been watching television nor too engaged on their smartphones, they were more alert, more open to talking about their day and generally more active.

CLOCKING KID-TIME

So how much time is actually spent with children these days? Suspicious of previous data based on estimates provided by mothers and fathers, the American researchers Rebelsky and Hanks installed microphones in the homes of parents of newborn children. They found that fathers, on average, interacted directly with their babies for 37.7 seconds a day! These fathers had thought they were spending at least fifteen to twenty minutes a day with them. Burgess reports that these findings have been recently reaffirmed by similar tests.

In a study entitled ‘Facilitating Future Changes’, J.H. Pleck and M.E. Lamb discuss research into the possible sources of men’s low participation in family life compared to that of women. This suggests that men’s work is not by itself a sufficient explanation. The amount of time they spend in paid work does have an impact on the amount of time spent with the family. Other social factors such as taking after one’s own father, social attitudes, lack of support from wives or peers and inadequate parenting skills also play a part. But even allowing for these influences, the main reason why men spend so little time with their families appears to be that they don’t really want to go home.

Other researchers have found that the tension between work and family is heightened when both elements are strong, though one will always ultimately prevail. On the other hand, if an executive feels a much stronger pull towards his work commitments than to his family, then no amount of pressure from his spouse or children will make him change his ways. Only if he is really sensitive to the importance of his family responsibilities will he put them ahead of his work. Often it depends on the relative rewards they offer. Work provides very clear and easily recognised rewards—money, power and possibly fame. The rewards offered by home and family are less easy to measure, except by such intangible factors as the development of a close relationship between a father and his children by establishing an intimacy with them in their early years that continues through the difficulties of adolescence and hopefully survives into their maturity and the rest of their lives. That in itself is its own reward.

MEN AND WOMEN: DIFFERENT WANTS

In a society with so many conflicting and confusing modes of behaviour it is hard to determine what people really want to do with their lives. According to the sociologist H. Glezer, in an article on ‘Juggling Work and Family Commitments’, when parents were asked whether they would prefer to work full-time, part-time or not at all, eighty per cent of men preferred full-time work, fifteen per cent part-time and five per cent said they would prefer not to work. However, only eighteen per cent of women wanted full-time work, with fifty-eight per cent preferring part-time work and twenty-four per cent saying they would rather not be in employment at all. It would appear that men were doing what they wanted to do—that is, working full-time—while the majority of women would have been happier in part-time work.

In an interesting study, L.Duxbury and C.Higgins investigated differences between the sexes in their attitudes to the question of work and family. They found that women are more likely than men to:

• put family demands before personal needs;

• feel guilty if they perceive that their role as provider takes away from their time as nurturer;

• exhibit greater concern and stress if they feel that they are neglecting their partners.

Men will be more likely than women to see being a good provider as key to their role in the family. They will also be more likely to think that their family interferes with their work.

HOME MUMS AND CAREER MUMS

Australian society is increasingly tending to devalue the work of raising a family. In what are meant to be enlightened times, women who choose to spend time at home rather than pursuing a career are often looked at as having given up their real calling. In the process of making sure that women have a choice when they become mothers, we have subtly suggested that women who work outside the home rather than at home raising kids are somehow smarter and more valuable. We should support both choices, but I fail to see how choosing to spend one’s time helping develop the next generation is not in fact the most valued job.

I recall having a heated argument a few years ago with a lawyer friend of mine. She had chosen to continue work when she had a baby, while my wife had chosen to stay at home and look after the children. My lawyer friend asked what my wife did. I replied that she was at home with the children, to which the lawyer responded: ‘Is that all?’ I guess in retrospect she was just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

We then spent quite some time discussing the relative merits of working mums versus ‘at home’ mums. What was most annoying about the discussion was that she could not accept that deciding to stay at home with your children was a choice that some women make and that this choice should not be seen as having ‘taken the easy road’. Her position was that she needed to work and that she couldn’t imagine ‘wasting her talents’ by staying at home with her children. I applaud women who are able to balance a successful work life with the responsibility of raising children–especially in a society that continues to place the major responsibility for child rearing on the mother.

At the same time, I do not accept that there is any ‘right’ choice. While applauding working mums I also applaud mums who decide that the best use of their skills and energy is to stay at home with their children. This is in no way an easy choice. It is one that takes a woman out of an environment (work) where rewards are clear and each day has structure. She is removed from an environment of continual contact with adults and one where she can have some independence. The choice to stay at home is a very hard one. The ‘stay at home’ mum has determined that while she is making significant trade-offs in her life she is doing the best for her children. While ensuring women continue to have the choice we must establish a more balanced approach to valuing the choices made.

A MOTHER’S ROLE?

For some time, I have watched the way in which stay-at-home mothers were being looked down upon by the ‘career’ mothers who were able to hold down a major job and be a great mum. Nobody is standing up to defend the mothers who really believed they were doing the best thing for their families by being at home for them. There are no business-suited, well-coiffured corporate women defending their choice with any passion. The issue is not in fact which way of life is better, but executive mothers and their supporters should accept that being a mother at home is perhaps just as important a role as any corporate job. In The Time Bind Hochschild found that implicit in work-family conflict at Amerco was the devaluation of the work of raising a family. As a consequence, individuals studied consciously tried to escape the work of child rearing in favour of the paid work environment.

HAVING IT ALL

Assume for a moment that you wanted to pursue two distinct careers, say medicine and being an economist. I think it is safe to say that other than for a few extraordinary people it is unlikely that you could excel to the best of your ability in medicine while, at the same time, be the best economist going around. Chances are you might be very good at both careers but not the best at either and furthermore, it is probably fair to say that if you had focused on one career you would have achieved greater development and success than if you tried to spread your energy and time across two.

I think this is the same between working mums or dads and stay at home mums or dads–particularly for children up to and including the child’s time at school.

If you are trying to excel at being the best you can at work then it is likely that you will be expected to work longer hours than most, take on more complex task than others, travel more than others and generally be seen to be and actually commit more of your waking hours to the role.

If at the same time you are trying to be a very involved parent then this means spending more time with your kids, taking on more child focused roles (school drop offs, school reading, sports coaching, canteen duties, managing after school homework, driving kids to after school activities) and generally allocating more of your energy and time to trying to be an involved parent.

Clearly you can’t do both to their individual extremes. Assuming your career is one that requires long hours then you can’t excel to the highest level in your career and at the same time allocate enough time to be the best parent you possibly can. Something has to give and you can’t have it all.

The best you can hope for is achieving an acceptable level of success in your career while also feeling as though you are truly delivering as an involved parent.

Sadly, given our work roles seem to be more obviously demanding on our time, it is very easy to allow work to suck up more and more of our time and we are therefore allocating less and less time to our children and families.

WRAPPING UP

This chapter has been arguing that we are on the wrong track. The facts speak for themselves: the decreasing time spent by fathers with children is having a detrimental effect on children. Further, children are not developing an ability to understand the role of fathers and men in society because fathers are so seldom with them. The values we are promoting in our society are more focused on economic wealth than on any sense of social wellbeing. We are allowing ourselves to be sucked into believing work and money are in fact the most important things in life. They are not.

What is most important in life is the way one looks at and takes care of one’s family, in the broadest sense. If we truly believed in the importance of looking after our children and each other and we were prepared to act accordingly, the world would be a better place. If fathers took more responsibility for their children, spent more time with them and opened their hearts to them, and to their spouses as well, we would be well on the way to creating a better and more humane world. It is as simple and complex as that. If you take only one thing from this chapter, let it be the point that as a father you have a responsibility to your children and yourself to spend more time with them and opened their hearts to them, and to their spouses as well, we would well be on the way to creating a better and more humane world. It is as simple and complex as that.

If you take only one thing from this chapter, let it be the point that as a father you have responsibility to your children and yourself to spend more time with them. You and they alike will benefit from this commitment.

Purchase a copy of Father Time

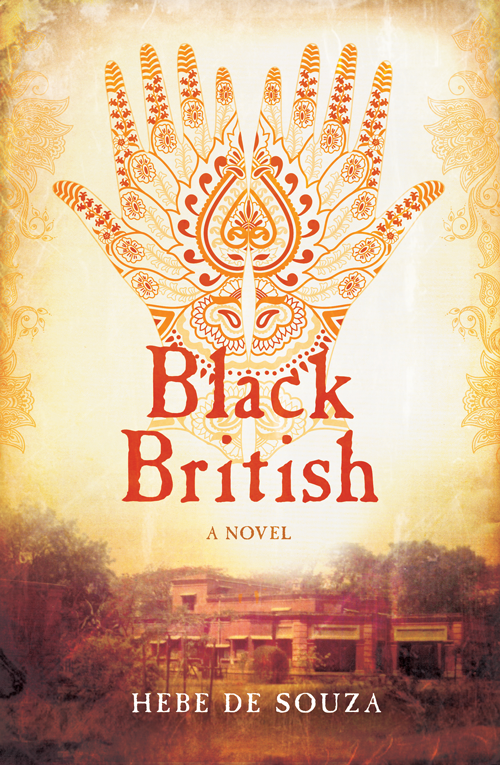

An extract from Black British by Hebe de Souza

In the turbulent years that follow the British Empire’s collapse in India, rebellious and inquisitive Lucy de Souza is born into an affluent Indian family that once prospered under the Raj. Known as Black British because of their English language and customs, when the British deserted India Lucy’s family was left behind, strangers in their own land.

A richly visceral and stunning debut, based on the author’s own childhood, Black British is an unflinching and beautiful narrative about feminism, family and the search for identity.

Read an extract below.

In the turbulent years that follow the British Empire’s collapse in India, rebellious and inquisitive Lucy de Souza is born into an affluent Indian family that once prospered under the Raj. Known as Black British because of their English language and customs, when the British deserted India Lucy’s family was left behind, strangers in their own land.

A richly visceral and stunning debut, based on the author’s own childhood, Black British is an unflinching and beautiful narrative about feminism, family and the search for identity.

Read an extract below.

1958

The magical day when the birthing stork dropped me in a Scottish Hospital in Kanpur, India, was 29 November, the day before St Andrew’s Day. Saint Andrew is the patron saint of Scotland and though it was eleven turbulent years after independence from the British Raj, he was still the patron saint of the Georgina MacRobert Memorial Hospital.

My sister Lily was born on St Andrew’s Day two years earlier but since she had the good sense to choose a hospital that had no connection with Scotland her birth caused no more than the usual tamasha.

But my birthday upset my mother. As she often said: “I wanted you to be born on your sister’s birthday. That way I’d have continued the trend set by my mother who had my sisters, Elsie and Tilly, on the same calendar day, two years apart. But you upset the apple cart and came a day early, causing endless confusion.

Her theory was that I was afraid if I waited for St Andrew’s Day my birth would go unnoticed in the frenzy of song and dance to celebrate the patron saint’s day.

“You upset so many people. Important people.” Ticking it off on her fingers she continued, “The hospital wasn’t ready, the doctor had the day off, your father was at his mill, there was no one to look after Lorraine and Lily…” She’d run out of steam.

And confusion there was.

The obstetrician was playing golf and feeling very pleased with himself because by the eighth hole his game was going better than that of his companions. He was poised for a birdie and having shuffled his feet, wriggled his bottom to ensure he was in the perfect position to effect a perfect shot, he gripped his putter with fierce concentration and that’s when the aaga- walla, the young servant employed to keep an eye on the ball, arrived with the summons.

“Sahib! Aou jow juldhi, quicklyquickly come. Baby coming. BABYCOMING.” The lad’s voice rose to a squeak as he leaned forward and pranced around energetically to add urgency to his already urgent words.

It took a few seconds before the obstetrician tore his focus away from his game and absorbed the news. Thinking from the aagawalla’s panic that my mother was at death’s door he dropped his golf club and ran all the way to the clubhouse, it being the days before golfing buggies. Arriving on the front verandah gasping for air, his face cherry-red, he was met by a gaggle of post-colonial memsahibs, elderly matrons who were consumed by their status as married, white, upper-class women.

These women decided he was ill and insisted on minis- tering to him. “Dr Aitkens! You shouldn’t be running around at your age.” Mrs Stott, the wife of the State Bank Manager, borrowed status from her husband’s position and appointed herself spokesperson of her cronies. With a singular lack of tact she added, “You are not a young man anymore!” Armed by her third tipple of gin-and-lime for the morning she was intent on doing her good deed for the day.

Calling for water, “Bearer, pani loa. Now!” And as though he was helpless, she insisted on holding the glass while he sipped. At the same time she attempted to mop his brow. Unfortunately, her alcohol-induced tremor meant that most of the water landed on his shirtfront so that by the time he arrived at the hospital his usually immaculate image was gone and he was dishevelled. My birth was also safely over and he had missed his opportunity to show off an expertise that is so unnecessary in an uncomplicated birth.

The second breathless messenger found the midwife at a tailor’s shop. She was clutching a grab-rail, desperately trying to maintain her balance on a three-legged stool while having the hem of her new dress pinned. My father was at his mill, and my sisters Lorraine and Lily took full advantage of adult distraction to ensure they were underfoot.

“Biscuit!” Lorraine was peremptory with our ayah, the nursery maid who had charge of them. Though she was only four years old she recognised an imbalance of power.

“Hungry!” wailed Lily, happy to learn a naughty lesson. But before the biscuit tin could be opened Lorraine jumped up and hit it with such force that the lid shot off and ginger- nuts flew in every direction.

“Run!” she shrieked, and grabbed biscuits in both hands before she tore through the dining and drawing rooms to the library. “In here. She won’t fit in here.” And Lorraine dived under my father’s desk with Lily close behind.

Biscuits gorged, helpless giggling at their temerity in the face of futile pleas from the ayah “to come out, baba,” soon subsided into boredom.

“It’s dark in here.” Lily showed signs of capitulation and that’s when Lorraine found inspiration from the wastepaper basket.

“We were making confetti,” she explained later with an air of surprise, because apart from ignorant adults, everyone knew that’s what little girls do when they are ensconced under a desk in close proximity to scrap paper. But no wild feat of imagination could explain how so many tiny shreds of paper got into so many cracks and crevices in one small room.

Somehow the responsibility for their behaviour was laid at my door.

As were several other legacies that resulted from my early birth. My mother lost her opportunity to follow the pattern established by my grandmother; the obstetrician’s best golf game ever was spoilt – a point he re-emphasised each time I met him in church in subsequent years until he left Kanpur to try his golfing prowess in greener pastures; and for causing the midwife to attend the St Andrew’s Day dance wearing the previous year’s dress. She insisted that was the sole reason her boyfriend Alex McKenzie married her best friend instead of her, and was later killed serving on the North West Frontier. The implication was that I was ultimately responsible for the midwife’s ex-best friend’s early widowhood.

I take a deep breath, recognising I’ve talked a lot. Should I continue? I’m supremely aware that I’m baring my soul to someone I’ve never set eyes on before. Sitting on the stone bench beside me he continues to look towards the church and appears comfortable and at ease.

I stretch my legs and look up at the cobalt sky of Goa, so alike and yet so different from the skies of Kanpur.

Maybe I’ve said too much? As though he can read my mind, my companion chuckles.

I pause for a moment.

Then I chuckle too. “You know, my family come from Goa,” I tell him. “In fact, from this very village.”

“Tell us a story, Daddy. Tell us about when you came from Goa.” Lorraine, Lily and I were past masters at pestering our father.

My father sighed. Repeated renditions had robbed the story of all romance. “I was born in Kanpur,” he said, “in this very house. So was your Aunt Arabella, Uncle Claude, Aunt Moira and Uncle Richard. Our ancestors came from Goa and settled here a long time ago. Our name, ‘de Souza’, comes from Goa.”

“Why?” That ubiquitous question that all children ask.

“I don’t know why they left Goa. It was around a hundred years ago so the story is forgotten. I presume it was grinding poverty. It must have been, for why else would anyone leave their home that is dear and familiar, to come to…this?” Sitting on the front verandah on hot summer days he’d shake his head in disbelief as we looked out on the dry, dispirited plains that couldn’t support a blade of grass.

But a different theory came from my Great Uncle Hugh who had independent rooms in our house and therefore was a pronounced influence on our lives. “It was probably adven- ture and enterprise that drove them. Goa is fifteen hundred miles southwest of Kanpur so not a journey for the foolhardy, especially in those days.” Opening the atlas, he pointed out the journey they would have taken.

“And when you consider that everything was so different for them. They spoke Konkani not Hindi, which is spoken here. We’re Catholics whereas the local people here are Hindus, their culture was different, this horrendous climate was… eh…horrendous, and yet they flourished. It says some- thing favourable about the calibre of our ancestors.” Uncle Hugh looked lost in thought over that epic journey.

At the time Goa had been a Portuguese colony for over 300 years, since 1510, and development had been stymied. In such a climate it only takes one restless person to stand on tiptoe, yearning for a glimpse of the worlds hidden beyond his horizon; one person with the hunger for adventure and the excitement of the unknown; one person with persuasive lead- ership to inspire his brothers, and family history is rewritten.

It only took one person – and that one person was my grandfather.

Or was it his grandfather? Or the one in between?

When a girl grows up steeped in family history details get lost. Like most children, my sisters and I took our background for granted.

My father took up the story, “Your great-grandfather [plus or minus one or two] gathered his chattels into a single box and made the long, perilous journey north into what, for him, was the unknown. He walked for three days to reach the port of Panjim where he found a rowboat to get him to the mainland. A bullock cart carried him to the edge of the hot, dry plains of Central India which he crossed by camel caravan. Another long walk took him through the last stage of his journey – a journey that was to change his life forever and the lives of his children and his children's children.

The enormity of the undertaking kept us silent for a while until Lorraine asked, “Wasn’t he sad to leave his home?”

My father considered this. “I don’t know what he felt as distance shrank the view of his family and home. I don’t know if he realised he’d never speak his melodious language again or that his children would adopt a different culture, a ludi- crous language and never call Goa home.”

My father looked so distracted over the poignancy of the story that all three of us sensed the desolation a mother would feel when she realised she’d go to her grave without another sight of her son; that her family, who had thrived on their Goan plains for hundreds of years, was dying out, their songs forever silent, their dances long forgotten and their home- distilled feni undrunk.

"Why did he come so far?

“Kanpur had been decimated after the First War of Indian Independence in eighteen fifty-seven so there was a flurry of activity to rebuild. The fertile soil and abundant water just six hundred feet underground meant the town was ripe for development. Kanpur’s position on the Ganges made trade easy. There would have been opportunities galore.”

Taking advantage of every opening my great-grandfather (plus or minus one or two) showed rare genius and pros- pered. He must have been an honourable man because, as he found his feet, he sent for his nephews from Goa and set them up with their own futures so the number of relations living around the Kanpur cantonments increased and I grew up surrounded by an odd assortment of aunts – and a few even odder uncles.

We’d heard this legend many times before and now, at the age of eight, Lorraine made connections beyond our tiny world.

“Are you glad they came to Kanpur?”

My father answered promptly. “I’m grateful for their success, which gave me opportunities I wouldn’t otherwise have had. I’m grateful I can provide magical lives for my precious daughters. But now I’m worried because though we are native by blood, birth and skin colour we are foreign by language, creed and culture. Our mother tongue has been English for generations, we’re Judeo-Christian in our beliefs and values and we dress in western clothes. Though the British Empire is now defunct old sins cast long shadows so the local people see us as remnants of their oppressive regime with no place in a modern India.”

In the national upheaval and chaos that invariably follows the demise of a great power, some of the local people found interesting ways to convey this message to us so that we lived with ever-present threats to our personal safety. That made us prisoners in our own home: willing porisoners, but prisoners nevertheless, isolated from people around us and marked as different. With dwindling fortunes our lives were a portrait of sepia, little more than witness to an iridescent past.

Purchase a copy of Black British by Hebe de Souza here:

Publishing a Book? How to make your manuscript stand out to a publisher

As one of Australia’s leading independent publishers, Ventura Press are constantly receiving manuscripts from a variety of authors. We thought it would be great to share with you the key factors that make a submission stand out.

We've asked our Publishing Manager, Jasmine Standfield, to tell us what she and the rest of our team look for when they're meeting for the first time with an author.

Below is an example of the kind of emails we receive on a day-to-day basis. It shows how crucial clarity, information and tone are to reaching your audience – both publishers and future readers. This is an example of what NOT to do:

Hi there,

I would like to talk to a hire-up in regards to a novel I am completing. My name is XXXX XXXXXX, I am located in XXXXXXX, and I would prefer to get in touch with Jane Curry, a chance to give her a brief synopsis of my fiction novel. I know it is nearly impossible to get in touch with someone that can help you with publishing a novel, however I know I have more to offer than any author, just looking for a chance.

Thank you for your time, please reach by email or phone anytime.

Best Regards,

The following tips are some of the things we love to see from authors and should help you write an engaging pitch to a prospective publisher:

Begin with the crucial information…

First of all, it is so important to put your name and the title of your manuscript in the very first line of your email. It’s also very important that the document or file you attach is correctly named so we don’t lose it on our database. Other information that is crucial in your email is your point of difference. Don’t just allude to it, tell us what it is. What makes you stand out from the 5000 other authors writing and submitting content every month? This of course includes your author platform.

Your author platform…

There is a huge difference between a good author who lives in an isolated area with an active blog and presence on Goodreads, and a brilliant author from Sydney who has never heard of Booktopia and doesn’t have time to write a blog or run their social media. Authors, we hope by now, are aware how important their platform is – this is the way that you communicate with your potential buyers. Your main focus is your one book, or your one series of books. A publisher will likely be working on 24 books at once so can’t possibly dedicate the time to, or understand, your audience as well as you can.

Write a Pitch Sentence…

It sounds obvious but please tell us, clearly, what your book is about. Our house has a saying; ‘The pitch starts with you’. If you can’t explain to us what your book is about in a short and clear manner, how will we be able to pitch it to the sales reps, who then pitch it to the book buyers, who then pitch it to their staff, who then pitch it to the potential buyer on the shop floor? A long-winded synopsis gets lost in translation.

Include comparison titles…

Competitor analysis is also crucial. Please try to avoid the words ‘There is no other book like this out there’, because there almost definitely is – and this is a positive. This means that we can link your work to an established genre, tailoring your marketing to the right readers and positioning you in the market correctly. Think ‘The next Arianna Huffington’ or ‘A cross between Hunger Games and Harry Potter’.

Keep a balanced tone…

Be confident, but not arrogant. You are not the only person who has worked with Kerry Packer or met a celebrity.

And above all…

Be specific. Your cover letter is your elevator pitch and your media release. Put your strongest points at the top, best foot forward. Each cover letter or email should also be specifically tailored to the type of book you are pitching. For example, if you are pitching a book about leadership and success or work-life balance, don’t start the letter about where you are located or how many kids you have. Start with ‘As one of the top 100 part-time workers in Australia, I would like to introduce you to my business book about XYZ’.

Below is an example we have created of how to professionally pitch a fiction title:

Dear Ventura Press,

My name is Sarah Morton and I would like to pitch, Strangers Passing By, a contemporary fiction novel set in the beautiful landscape of the iconic Blue Mountains.

The book explores the romance and tragedy of Julie Graham, who works at a Post Office following the death of her father in WWI. It is based on the true story of my great Aunt, whose letters and diary entries were discovered when she passed away five years ago.

Strangers Passing By would suit the Australian Literature or Historical Fiction genre and stands out from other titles as it includes original photographs of handwritten letters within the pages acting as points of departure for each chapter.

The book also explores themes of feminism, marriage, Indigenous culture and religion in ways that could be compared to My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin and The Getting of Wisdom by Handle Richardson.

I have been published with literary journals A, B and C as well as online publication D. My author platform includes my blog which has a following of X, and my Facebook and Twitter accounts have Y followers. I have media contacts at Z, who would be happy to help me promote my novel. I also have a friend, X, who is a published author who said he would be happy to write a forward.

Please see attached the Synopsis, a Sample Chapter, Author Platform details and Competitor Analysis.

Thank you for your time, I look forward to hearing from you.

Sarah Morton

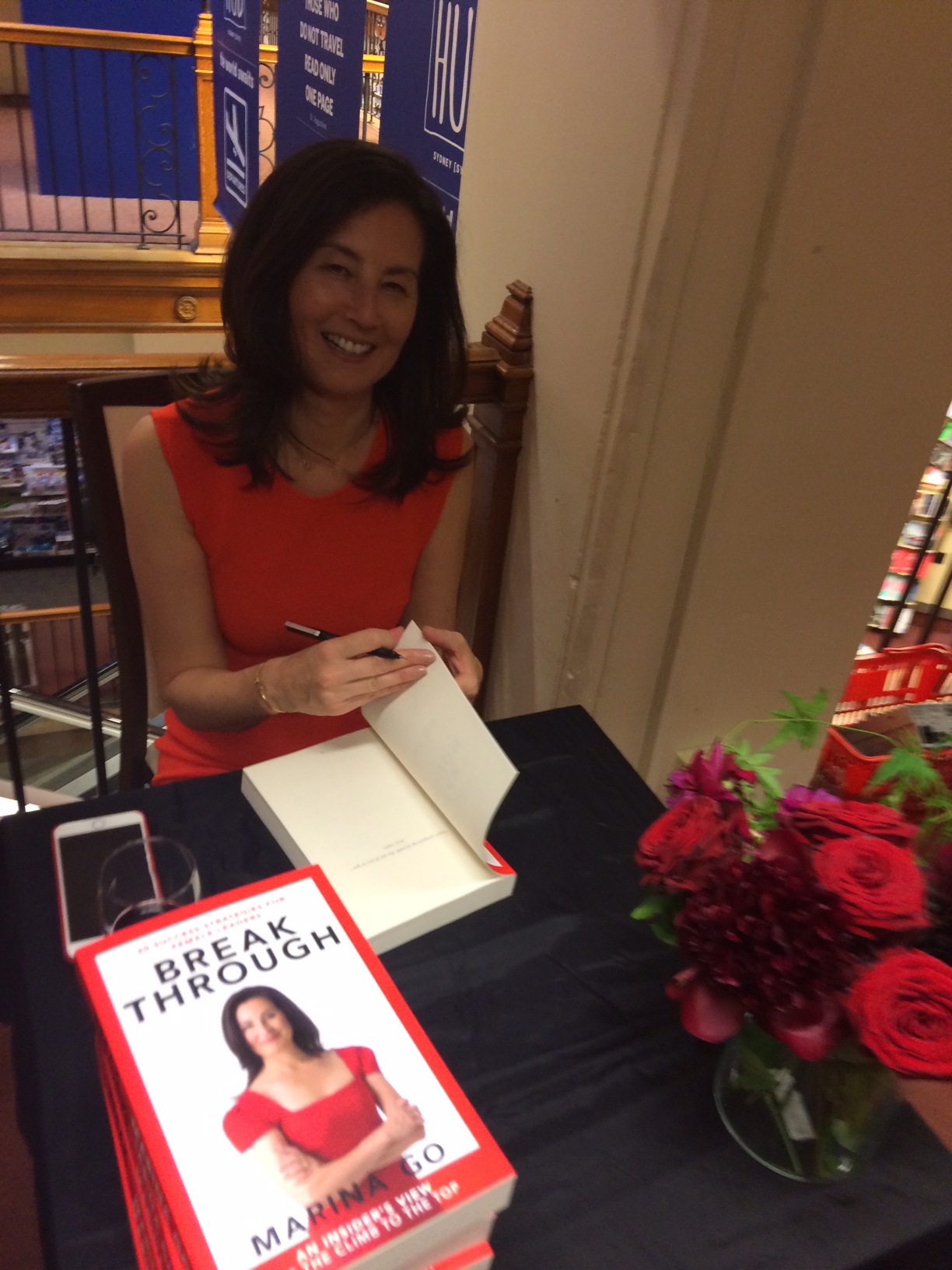

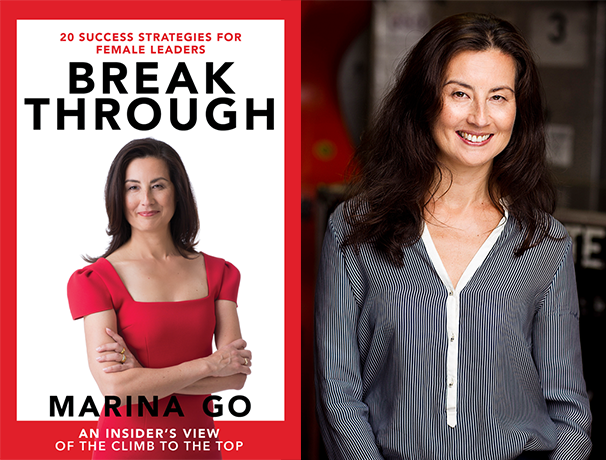

Listen to Marina Go on So You Want To Be A Writer, the Australian Writer's Centre podcast

The Australian Writer's Centre podcast, So You Want To Be A Writer, hosted by Valerie Khoo and Alison Tate, have just released their latest podcast featuring an interview with Marina Go, author of Break Through: 20 Success Strategies for Female Leaders and General Manager of ELLE, Cosmopolitan and Harper's Bazaar. The podcast is a vital resource for all writers, discussing writing tips, publishing and careers.

In Episode 108, Marina talks to Valerie about the writing process behind Break Through, the moments that lead to her decisions on the genre and structure, the plans she set out for herself and the challenges she faced when including other people’s personal lives in her story.

Valerie Khoo gave a wonderful review of Break Through, saying 'I read it in one sitting … I was eating my dinner as I was turning the pages…I couldn't put it down.'

Marina spoke about why she was so passionate about writing the book 'aimed at the next generation of female leaders'. She wanted to give these young women advice on how to tackle adversity and give them confidence to face the roadblocks in their career. Marina said she kept asking herself, 'how am I going to keep young women, millennials, entertained?' and came to the decision that ‘they will enjoy the tales and anecdotes of my career', which include run-ins with Kerry Packer, the glamorous trials and tribulations editing Dolly magazine at 23 years old, and plenty more stories that could be straight from the set of ABC's Paper Giants.

You can listen to the whole So You Want To Be A Writer podcast here - Marina's interview can be found at 23.00. Find out more about Break Through here, and read an excerpt of the book on our blog.

Break Through: 20 Success Strategies for Female Leaders is published by Ventura Press. RRP $32.99.

REBELLIOUS DAUGHTERS receives four star review from Books+Publishing

A recent write-up in Books+Publishing has awarded our Rebellious Daughters a four star rating, citing among the reasons; the books’ stellar line-up of Australian female writers, the considered editing by Maria Katsonis and Lee Kofman and the sheer range of featured works - from comical tales and essays to intimate and powerful memoirs.

A powerful, funny and poignant work, we couldn’t agree with them more. Rebellious Daughters explores everything from getting caught in seedy nightclubs to lifelong family conflicts and marrying too young, all told from the perspective of some of Australia’s most talented female writers. Read below for the full write-up from Books+Publishing.

Rebellious Daughters features a stellar line-up of Australian female writers sharing touching stories of rebellion, family life, coming of age and motherhood. Edited by Maria Katsonis and Lee Kofman, this is a well-balanced collection of memoirs that charts the ‘complicated map of parent-daughter relationships’: from funny tales of youthful rebellion to traumatic estrangements and lasting wounds, the thrill of independence to unbreakable bonds and family loyalty. Rochelle Siemienowicz carves out a Self in a strict but loving Seventh-day Adventist household, and later fights against ‘the disappearing act’ women perform when they are consumed by motherhood. Rebecca Starford examines the risky business of memoir writing, questions of ownership and the idea of writing as rebellion. Susan Wyndham and Nicola Redhouse struggle to adjust to step-parents, while Krissy Kneen, the rebellious granddaughter, escapes her fairytale-obsessed grandmother to create her own tale of metamorphosis, sexual desire and freedom. One of the most poignant essays is Eliza-Jane Henry-Jones’ account of growing up in an atmosphere of decline, fighting against Alzheimer’s as she watches her grandmother and then her father forget themselves and their family. These intimate stories will appeal to readers of family memoir and essay collections such as Mothermorphosis.

Releasing 1 August 2016, click here to read more about 'Rebellious Daughters' as well as our other great titles.

A wonderful night at the book launch of Break Through by Marina Go

The launch of Marina Go’s debut title, Break Through, was met with resounding success. Last night, 130 guests gathered upstairs at Dymocks Bookshop on George Street to pick up their signed copy, mingle and have a drink.

Break Through was launched by Wendy McCarthy, who has been a strong supporter of Marina’s career for many years. Wendy opened the event by talking about her passion for Australian women and how important it is for women to maintain the drive to succeed and achieve positions of leadership. She congratulated Marina on producing such a unique and motivating page turner and read to us one of her favourite extracts from the book which you can read here.

Marina shared her secrets on the book-writing process, the deadlines that were required to pump out two chapters a day and the reasons behind her unique style and structure. Break Through is part memoir and part guide to success for business women. Marina confided that she never wanted to follow a traditional approach, but rather, she wrote a book for herself, including stories and advice that she would have wanted earlier in her career. In Break Through, she reveals her experience growing up surrounded by strong women, progressive attitudes and influential people that led to where she is today. Her gratitude to her parents was touching, she thanked them for their help during the writing process.

It was a thrilling to be in a room with so many successful, inspiring women including Ann Sherry, Helen McCabe and Tracey Spicer. It’s nights like these that make us all refreshed and motivated to keep on working hard back at the office—knowing the end result can be so spectacular and rewarding.

A huge thanks to Marina Go’s team from Bauer who brought beautiful finishing touches to decorate the bookstore and the team at Dymocks Sydney for having us.

A mother lode of brilliant books to gift this Mother's Day

Mother's Day is fast approaching! And to celebrate, here are some of our staff's top picks that we know our Mums will love. Whether she's a business woman, stay at home mum, an empty nester, a grandma or the motherly figure in your life--there's something for all Mums on this lovely list...

Between the Dances by Jacqueline Dinan

Heart Hungers by Winsome Thomas

Midlife Manifesto by Jane Mathews

The Little Book of Mum's Wisdom by Denis and Ian Baker

The Magic of Tea by Alice Parsons

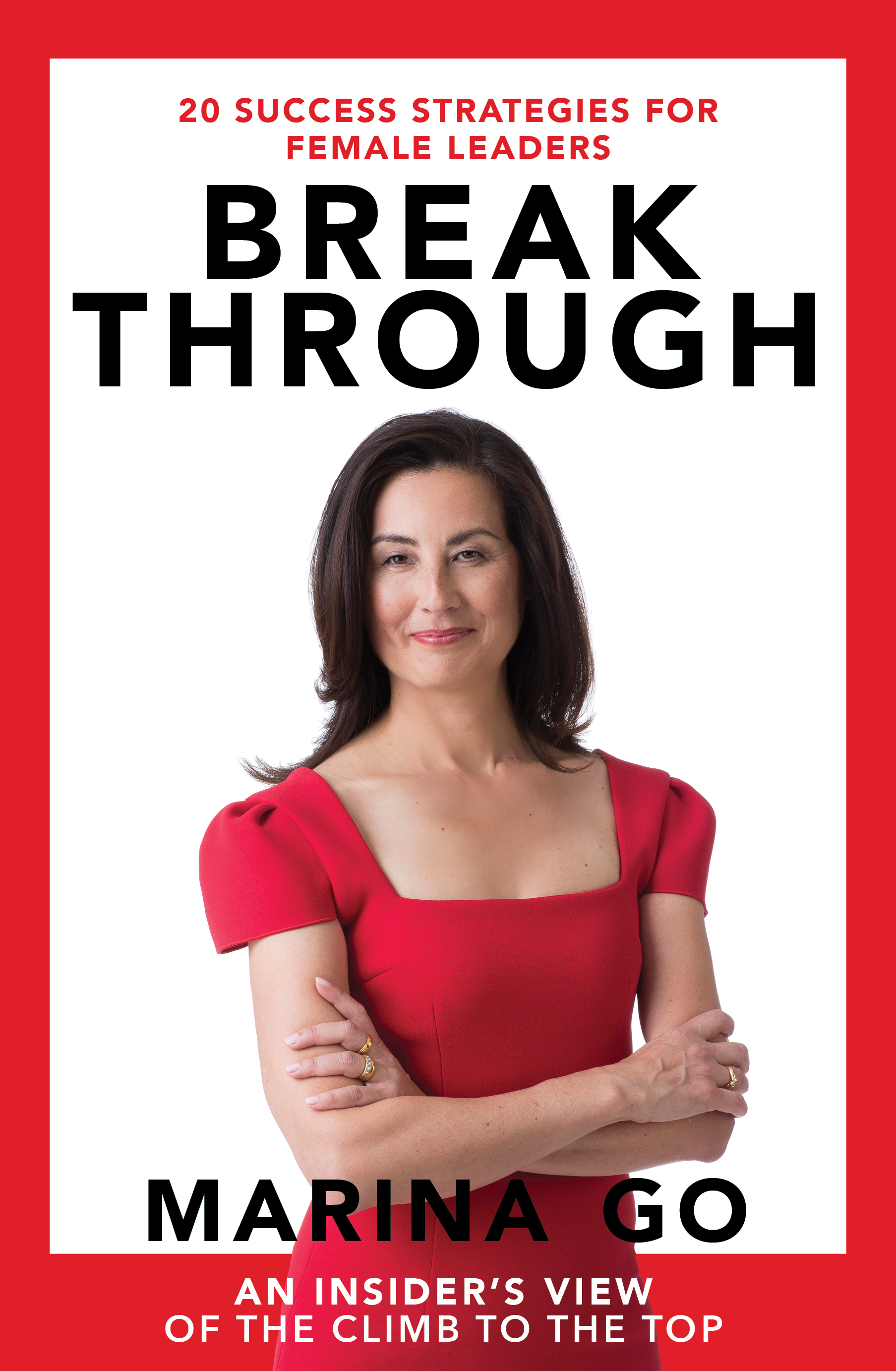

An Extract from Break Through by Marina Go

From editor of Dolly at the age of 23 to CEO of Australia’s leading digital publisher by her forties, Marina Go is here to inspire the next generation of female leaders to take their rightful place at the top. In Break Through, Marina Go, general manager of Harper’s Bazaar, ELLE and Cosmopolitan and the first female chair of Wests Tigers NRL Club, shares an in-depth analysis of the 20 leadership traits that make a successful woman – providing the tools to turn your personal vision of success into a reality.

Read an extract below.

From editor of Dolly at the age of 23 to CEO of Australia’s leading digital publisher by her forties, Marina Go is here to inspire the next generation of female leaders to take their rightful place at the top. In Break Through, Marina Go, general manager of Harper’s Bazaar, ELLE and Cosmopolitan and the first female chair of Wests Tigers NRL Club, shares an in-depth analysis of the 20 leadership traits that make a successful woman – providing the tools to turn your personal vision of success into a reality.

Read an extract below.

MAKE YOUR OWN LUCK

Leadership lesson: How to make the most of being in the right place at the right time

I have always believed we make our own luck.

Being in the right place at the right time is lucky, as is being born into a well-connected family or having access to family money when you want to start a business. However, it’s how well prepared you are when you get that lucky break that really counts. As a career strategist, I was never going to rely on charm to get me where I desperately wanted to go – which was right to the top.

From the time I was young my father told me I needed to set down solid foundations early in my career. He advised me there was no way around good old-fashioned hard work and study. He was the complete opposite of those people who pin their life’s hopes on winning the lottery. Dad loved the odd gamble at the races, but he never assumed he would win his way to wealth. He worked hard his entire working life and the financial decisions my parents made along the way are the reason they live a comfortable existence in their retirement.

I have built my career on the same principles. My career strategy has been to almost over-qualify for every role I aspire to.

This is also a very female thing to do, I know. But it does mean that when opportunity, or luck, strikes you are ready for it.

It also means that you may, in fact, create your own luck. If you are the standout candidate for a job, then, due to the career decisions that you made in the lead-up, you will undoubtedly be the person an astute organisation taps on the shoulder.

I felt extremely lucky when two years ago, out of the blue, I was offered the chance to run the Hearst business for Bauer Media. I couldn’t believe my luck.

But when I spoke to both the CEO of Bauer Media and the Head of International Licensing for Hearst about the role, it became evident that it was my career choices to date that had prepared me for that role. Hearst was in the middle of rolling out a global digital strategy and they wanted someone with extensive digital and magazine publishing experience who had a deep understanding of female consumers to lead their business in Australia. Apparently I was one of very few people who could tick all those boxes.

My career strategy has been to differentiate myself from the rest of my peers by making different career decisions and then adding postgraduate study to the mix. It’s one of the key reasons I have been able to break through into the executive ranks. But the strategy is equally important when you are starting out in your career.

I always tell the story of Dolly when describing my first lucky break. I had a simple, but focused dream as a teenager: to become editor of Dolly magazine. I worked out the steps it would take for me to get there. The steps were many, varied and definitely not assured. But I never gave up hope. I visualised myself in that role and always believed I would get it. Then I worked hard to reach my goal: a full-time day job and a full-time university study workload in the evenings. Nothing was going to stop me.

±

MEMOIR:

Lucky breaks – the who, what and where of landing the dream job of editor of Dolly magazine

The yellow batphone buzzed loudly and I almost fell off my chair. It was every editor’s nightmare – well, at least my editor was terrified of it. It was the direct line to management and if it buzzed, it was one of three people who could make your day – or ruin it: Publisher Richard Walsh, Editor-in-Chief Lisa Wilkinson or owner Kerry Packer.

The editor of Dolly was in the UK on leave and as her deputy I was keeping the seat warm and the magazine running smoothly until her return – planned for later that month.

I answered the phone and murmured nervously, “hello”. It was Richard, my favourite of the three potential callers.

“Can you come to my office? I need to discuss something with you,” he said, with a definite lilt in his voice.

Certain he wanted to discuss the latest issue or next cover, as copy sales had been sliding in recent months, I gathered up my entire desk, virtually, and hurried anxiously along to his office. Even though I was only the acting editor, I was keen not to make any mistakes. When I arrived, Richard’s door was open and he invited me in.

Not one to waste time, Richard got to the point immediately. “Caroline’s not coming back to Dolly and I’d like you to be the editor,” he said with a wide grin. I was speechless, but absolutely bursting with joy inside.

Before I could say anything at all, he added, “Now go and see Lisa so she can talk to you about this.”

I couldn’t believe it. As a 16-year-old living in the suburbs, I would look forward to the day a new edition of Dolly was published – in the way that I now looked forward to buying a new pair of shoes with virtually the same frequency.

Of course I believed I could do it, no question. I’d planned out the ultimate issue of Dolly in my mind many times. As I walked – or was I skipping? – along the corridor to Lisa’s office, I was visualising the new Dolly. I am embarrassed to admit at this point that I was so excited I didn’t even consider that perhaps Caroline might have been pushed. I was so optimistic and, to be honest, completely green and naive in the ways of the magazine publishing world that I assumed she must have decided not to come back from London, which was her home town after all. It was my turn to be in the right place at the right time. I thought it was some sort of sign.

I had missed out on the editor’s job 10 months earlier when the decision came down to two people: Caroline and me. The rumour was that Lisa had chosen me and Richard had chosen Caroline, but neither of them ever actually confirmed that.

My father, one of the most superstitious people on this planet and probably the reason I consulted so many psychics and tarot readers over the years, told me it wasn’t meant to be.

“Don’t worry,” he said knowingly, when I phoned to say I didn’t get the job. “Your time will come.”

For some reason I always believed him when he said that. Even though in my heart I knew he only said it because he believed in me.

Caroline’s approach to the magazine was exactly aligned with the brief she’d been given when hired to edit the magazine: she packed the magazine with all the things she believed teenage girls should be passionate about – the environment, having a career, eating well and not wasting your time on petty things like hair removal or make-up. They were all really great things for young women to be concerned about. The problem was that teenage girls just weren’t interested in that alone and readers had given up on the magazine to the tune of 100,000 copy sales per month. It hadn’t helped that another teenage girl’s magazine, Girlfriend, which had a greater focus on sex and celebrities, had launched around the same time that Caroline became editor.

Thankfully Lisa and I shared a vision for Dolly – of course we did, she was my inspiration for choosing my career.